Reviewed by Stefanie Wortman

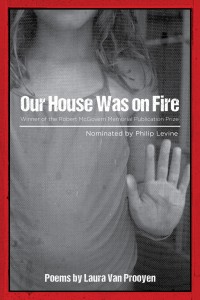

Our House Was on Fire, Laura Van Prooyen

Ashland Poetry Press

ISBN-13: 978-0912592794

$15.95, 76 pages

Laura Van Prooyen’s second poetry collection pauses in the middle of family life to consider the attachments we form and the paths that lead us to them. Our House Was on Fire concerns a love that has matured and a family that has grown to include children, but though the setting of the book is domestic, the voice of their speaker is anything but domesticated. These poems live in the conditional tense, admitting a feeling of tentativeness and even sometimes danger into what might appear from the outside to be a settled life. At their center is a woman who courts risk, as we see in the poem “Happiness”:

I am the girl who, long before you,

hopped on the back of some guy’s bike never thinking

he could drive me to the cornfieldand leave me there when he was through.

It doesn’t really matter that I ended upwith only a tailpipe burn. The point is I can’t quite say no.

For the speaker of this poem and this collection, house, husband, and children are not a conclusion to take for granted, and as she considers their place in her life, dreams and alternative possibilities seem not so much separate categories of existence as coexisting states that complicate and ultimately enrich the picture of a loving home.

What I have called the conditional mode of this collection begins with the first poem, “Migration,” in which the woman feels poised between two men, one who touched her all night and another, currently sleeping next to her. Waking from dream state into clearer consciousness might resolve any ambiguity about which is real, but Van Prooyen’s fragment “If / that was a dream,” with its line break deliberately emphasizing if, refuses to write off the first man as simply a fantasy. Whether or not the speaker encountered him in a dream, “she knew / to put her plume in his hand was never to go back.”

As in this dream poem, a former love shadows the collection, not only occurring to the speaker as a path not taken, but also making its alternative claims on her. “Intersection” considers where the speaker and this earlier love diverged, “where you did not kiss me, / where we did not stop.” In this poem, she is able to assert “Because I cannot call you, you / do not exist.” However, the separation doesn’t seem quite so simple in “Decade,” where a former lover’s imagining of the speaker’s future seems to color her present. Not only does her life resemble “the one you imagined” in actual details like “gauzy curtains” and a line of ripening tomatoes on the window sill, but it also contains apparitions that seem equally substantial: “Here, I live my life. The dog is only imagined. Yet / you go on stroking its fur.”

In these and other poems throughout Our House Was on Fire, love and sex multiply possibilities. Although this layering of past and current time, of actual and hypothetical states, might be disorienting to both speaker and reader, it also imparts richness to the world where we both live and imagine she lives. These interesting complications offer a counterforce to another of the collection’s thematic threads, the conclusive diagnosis of an illness in a child, which the mother understands will stay with her daughter for the rest of her life, no matter what paths or possibilities she follows. In “Undoing Her Hair,” illness introduces this child to a world where her mother cannot go. The “singing” in her ears, a “phantom” glimpsed in a hallway are reminders that “the more / the body fails, the more / the girl speaks of what / the mother cannot see.” One of the subplots of Our House Was on Fire is the young girl’s coming to understand the gravity of her chronic condition, to understand what her mother already knows about the unalterable future.

The imagery of these poems, like their grammar, supports Van Prooyen’s meditation on certainty and ambiguity. One metaphor often slips into another, drawing the reader along a chain of figures that might lead back to where they began. In the lovely “Pine,” for instance, the speaker’s “heart full of needles” yearns for a man she characterizes as “the stack of wobbly / coins…the train / shaking the rails” and possibly also “The pine / bent heavy with cones.” She reads a set of raccoon tracks as stars on fresh snow, but too self-aware to romanticize them further, she knows the animals were only “casing the house.” This deft collection of lyrics follows a quest into that “heart full of needles,” a search that readers will understand as more honest for admitting the obscurity it encounters.

Stefanie Wortman’s first book of poems, In the Permanent Collection, was selected for the Vassar Miller Prize. Her poems and essays have appeared in the Boston Review, Yale Review, Southwest Review, Pleiades, and other journals. She teaches at Rhode Island College. Find her on Twitter at @frettychervil.